Showing Spotlights 505 - 512 of 556 in category All (newest first):

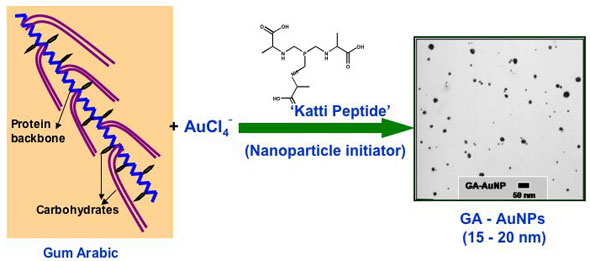

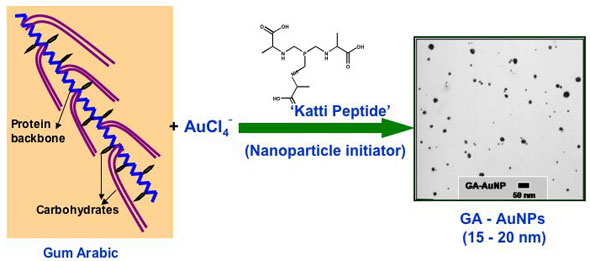

Gold nanoparticles have gained significant prominence in the design and development of nanoscale devices and nanosensors. The ubiquitous place of gold in nanoscience stems from its unique chemical property of serving in the unoxidized state at the nanoparticulate level. In sharp contrast, most of the surfaces of the less-noble metals are susceptible to oxidation to a depth of several nanometers or more, often obliterating the nanoscale properties. The high surface reactivity of gold nanoparticles, coupled with their biocompatible properties, has spawned major interest in the utility of gold nanoparticles for in vivo molecular imaging and therapeutic applications. The core of nanomedicine embodies high surface area and the size relationship of nanoparticles to cellular domains so that individual cells can be targeted for diagnostic imaging or therapy of cancer and other diseases. The development of biocompatible and non-toxic nanoparticles is of paramount importance for their utility in nanomedicine applications. Despite the huge potential for gold nanoparticle-based nanomedicinal products, nontoxic gold nanoparticle constructs and formulations that can be readily administered are still rare. Hypothesizing that the ability of plants to absorb and assimilate metals will provide opportunities to utilize plant extracts as nontoxic vehicles to stabilize and deliver nanoparticles for in vivo nanomedicinal applications, researchers now have used Gum Arabic as a plant-derived, nontoxic construct for stabilizing gold nanoparticles. The development of readily injectable, in vivo stable and non-toxic gold nanoparticulate vectors, especially built from currently accepted human food ingredients, would be pivotal in their many uses (e.g. in vivo sensors, photoactive agents for optical imaging, drug carriers, contrast enhancers in computer tomography, X-ray absorbers).

Gold nanoparticles have gained significant prominence in the design and development of nanoscale devices and nanosensors. The ubiquitous place of gold in nanoscience stems from its unique chemical property of serving in the unoxidized state at the nanoparticulate level. In sharp contrast, most of the surfaces of the less-noble metals are susceptible to oxidation to a depth of several nanometers or more, often obliterating the nanoscale properties. The high surface reactivity of gold nanoparticles, coupled with their biocompatible properties, has spawned major interest in the utility of gold nanoparticles for in vivo molecular imaging and therapeutic applications. The core of nanomedicine embodies high surface area and the size relationship of nanoparticles to cellular domains so that individual cells can be targeted for diagnostic imaging or therapy of cancer and other diseases. The development of biocompatible and non-toxic nanoparticles is of paramount importance for their utility in nanomedicine applications. Despite the huge potential for gold nanoparticle-based nanomedicinal products, nontoxic gold nanoparticle constructs and formulations that can be readily administered are still rare. Hypothesizing that the ability of plants to absorb and assimilate metals will provide opportunities to utilize plant extracts as nontoxic vehicles to stabilize and deliver nanoparticles for in vivo nanomedicinal applications, researchers now have used Gum Arabic as a plant-derived, nontoxic construct for stabilizing gold nanoparticles. The development of readily injectable, in vivo stable and non-toxic gold nanoparticulate vectors, especially built from currently accepted human food ingredients, would be pivotal in their many uses (e.g. in vivo sensors, photoactive agents for optical imaging, drug carriers, contrast enhancers in computer tomography, X-ray absorbers).

Feb 12th, 2007

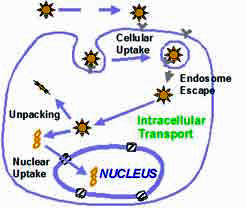

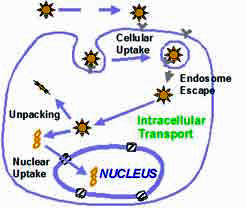

There is currently no cure for Alzheimer's disease and its ultimate cause is still unknown. The disease affects an estimated 4.5 million people in the United States alone. That figure is expected to rise dramatically as the population ages, experts predict. Genetic factors are known to be important in causing the disease, and dominant mutations in different genes have been identified that account for both early onset and late onset Alzheimer's. For a number of years, researchers have been working to alleviate neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer's or Parkinson's disease through gene therapy. In this type of treatment, a gene's DNA is delivered to the neurons in individual cells, allowing them to produce their own therapeutic proteins. Gene therapy typically aims to supplement a defective mutant allele (the location of DNA codings on a chromosome) with a functional one. Currently, the most common carrier vehicles to deliver the therapeutic genes to the patient's target cells are viruses that have been genetically altered to carry normal human DNA. These viruses infect cells, deposit their DNA payloads, and take over the cells' machinery to produce the desirable proteins. One problem with this method is that the human body has developed a very effective immune system that protects it from viral infections. Thanks to advances in nanotechnological fabrication techniques, the development of nonviral nanocarriers for gene delivery has become possible. This is attractive due to the potential for improved safety, reduced ability to provoke an immune response, ease of manufacturing and scale up, and the ability to accommodate larger DNA molecules compared to virus-based delivery tools.

There is currently no cure for Alzheimer's disease and its ultimate cause is still unknown. The disease affects an estimated 4.5 million people in the United States alone. That figure is expected to rise dramatically as the population ages, experts predict. Genetic factors are known to be important in causing the disease, and dominant mutations in different genes have been identified that account for both early onset and late onset Alzheimer's. For a number of years, researchers have been working to alleviate neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer's or Parkinson's disease through gene therapy. In this type of treatment, a gene's DNA is delivered to the neurons in individual cells, allowing them to produce their own therapeutic proteins. Gene therapy typically aims to supplement a defective mutant allele (the location of DNA codings on a chromosome) with a functional one. Currently, the most common carrier vehicles to deliver the therapeutic genes to the patient's target cells are viruses that have been genetically altered to carry normal human DNA. These viruses infect cells, deposit their DNA payloads, and take over the cells' machinery to produce the desirable proteins. One problem with this method is that the human body has developed a very effective immune system that protects it from viral infections. Thanks to advances in nanotechnological fabrication techniques, the development of nonviral nanocarriers for gene delivery has become possible. This is attractive due to the potential for improved safety, reduced ability to provoke an immune response, ease of manufacturing and scale up, and the ability to accommodate larger DNA molecules compared to virus-based delivery tools.

Feb 9th, 2007

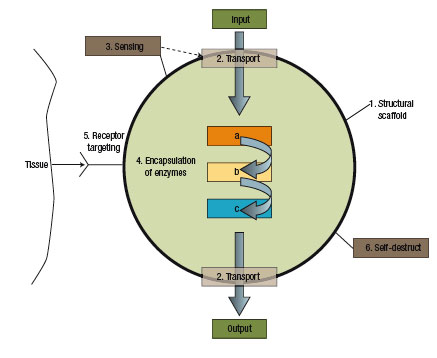

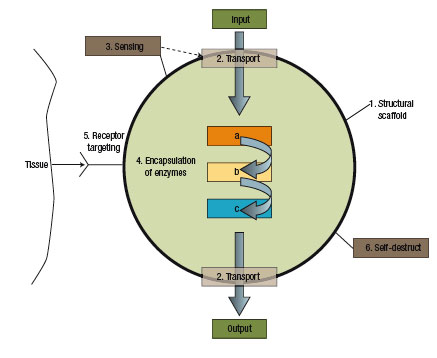

Without doubt, nanotechnology is having a major impact on medicine and the treatment of disease, notably in imaging and targeted drug delivery. Nanotechnology promises us a radically different medicine than the cut, poke and carpet bomb (think chemo therapy) medicine of today. The two major differences of nanomedicine will be a) the tools it uses - the main workhorse will be multifunctional nanoparticles and b) it will enable a perfectly targeted and individual treatment: organs and bones, really any body tissue, can be diagnosed and treated on a cell by cell basis with precise dosing and monitoring through the use of biomolecular sensors. Notwithstanding the huge amount of research going into this field, nanomedicine by and large is still in the basic research stage. Some fundamental problems like the targeting of nanoparticles in vivo, the transport of unstable drugs, and the dosage control of drug-carrying nanoparticles lead some scientists to think even one step further. Rather than delivering external drugs into the body, they conceptualize "pseudo-cell" nanofactories that work with raw ingredients already in the body to manufacture the proper amount of drug in-situ under the control of a molecular biosensor.

Without doubt, nanotechnology is having a major impact on medicine and the treatment of disease, notably in imaging and targeted drug delivery. Nanotechnology promises us a radically different medicine than the cut, poke and carpet bomb (think chemo therapy) medicine of today. The two major differences of nanomedicine will be a) the tools it uses - the main workhorse will be multifunctional nanoparticles and b) it will enable a perfectly targeted and individual treatment: organs and bones, really any body tissue, can be diagnosed and treated on a cell by cell basis with precise dosing and monitoring through the use of biomolecular sensors. Notwithstanding the huge amount of research going into this field, nanomedicine by and large is still in the basic research stage. Some fundamental problems like the targeting of nanoparticles in vivo, the transport of unstable drugs, and the dosage control of drug-carrying nanoparticles lead some scientists to think even one step further. Rather than delivering external drugs into the body, they conceptualize "pseudo-cell" nanofactories that work with raw ingredients already in the body to manufacture the proper amount of drug in-situ under the control of a molecular biosensor.

Feb 8th, 2007

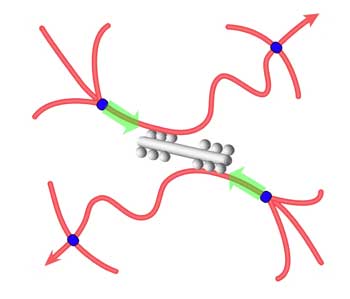

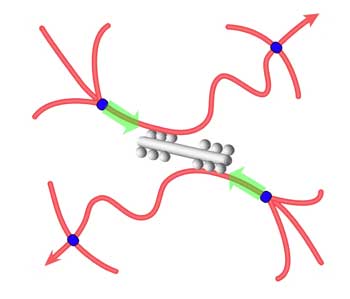

In much the same way that each of our bodies depends on bones for mechanical integrity and strength, each cell within our bodies is governed mechanically by a skeleton of composite materials including protein polymers (such as actin filaments) and motor proteins (myosin), called the cytoskeleton. Actin and myosin are key components in muscle contraction and cell motility. The cytoskeleton is an active material that maintains cell shape, enables some cell motion, and plays important roles in both intra-cellular transport and cellular division. The cytoskeletal system is not at thermodynamic equilibrium and this non-equilibrium drives motor proteins that are the force generators in cells. Analogous to how our bones are held and moved by muscles, the cytoskeleton is activated by these molecular motors, which are nanometer-sized force-generating enzymes. In an ongoing effort to design and create a simplified, bottom-up model of the cytoskeleton, researchers now have designed and assembled a biomolecular model system capable of mechanical activity similar to that of living cells. This work could serve as a starting point for exploring both model systems and cells in quantitative detail, with the aim of uncovering the physical principles underlying the active regulation of the complex mechanical functions of cells. It could also provide new fundamental insights and offer new design principles for materials science.

In much the same way that each of our bodies depends on bones for mechanical integrity and strength, each cell within our bodies is governed mechanically by a skeleton of composite materials including protein polymers (such as actin filaments) and motor proteins (myosin), called the cytoskeleton. Actin and myosin are key components in muscle contraction and cell motility. The cytoskeleton is an active material that maintains cell shape, enables some cell motion, and plays important roles in both intra-cellular transport and cellular division. The cytoskeletal system is not at thermodynamic equilibrium and this non-equilibrium drives motor proteins that are the force generators in cells. Analogous to how our bones are held and moved by muscles, the cytoskeleton is activated by these molecular motors, which are nanometer-sized force-generating enzymes. In an ongoing effort to design and create a simplified, bottom-up model of the cytoskeleton, researchers now have designed and assembled a biomolecular model system capable of mechanical activity similar to that of living cells. This work could serve as a starting point for exploring both model systems and cells in quantitative detail, with the aim of uncovering the physical principles underlying the active regulation of the complex mechanical functions of cells. It could also provide new fundamental insights and offer new design principles for materials science.

Feb 6th, 2007

Nanotechnology-enabled tissue engineering is receiving increasing attention. The ultimate goal of tissue engineering as a medical treatment concept is to replace or restore the anatomic structure and function of damaged, injured, or missing tissue. At the core of tissue engineering is the construction of three-dimensional scaffolds out of biomaterials to provide mechanical support and guide cell growth into new tissues or organs. Biomaterials can be variously permanent or biodegradable, naturally occurring or synthetic, but inevitably need to be biocompatible. Using nanotechnology, biomaterial scaffolds can be manipulated at atomic, molecular, and macromolecular levels. Creating tissue engineering scaffolds in nanoscale also may bring unpredictable new properties to the material, such as mechanical (stronger), physical (lighter and more porous) or chemical reactivity (more active or less corrosive), which are unavailable at micro- or macroscales. For bone tissue engineering, a special subset of osteoinductive, osteoconductive, integrative and mechanically compatible materials are required. Such materials need to provide cell anchorage sites, mechanical stability, structural guidance and an in vivo milieu. Moreover, they need to provide an interface able to respond to local physiological and biological changes and to remodel the extracellular matrix (ECM) in order to integrate with the surrounding native tissue. Scientists in Singapore have developed a new nanoscale biocomposite that brings researchers one step closer to mimicking the architecture of the ECM.

Nanotechnology-enabled tissue engineering is receiving increasing attention. The ultimate goal of tissue engineering as a medical treatment concept is to replace or restore the anatomic structure and function of damaged, injured, or missing tissue. At the core of tissue engineering is the construction of three-dimensional scaffolds out of biomaterials to provide mechanical support and guide cell growth into new tissues or organs. Biomaterials can be variously permanent or biodegradable, naturally occurring or synthetic, but inevitably need to be biocompatible. Using nanotechnology, biomaterial scaffolds can be manipulated at atomic, molecular, and macromolecular levels. Creating tissue engineering scaffolds in nanoscale also may bring unpredictable new properties to the material, such as mechanical (stronger), physical (lighter and more porous) or chemical reactivity (more active or less corrosive), which are unavailable at micro- or macroscales. For bone tissue engineering, a special subset of osteoinductive, osteoconductive, integrative and mechanically compatible materials are required. Such materials need to provide cell anchorage sites, mechanical stability, structural guidance and an in vivo milieu. Moreover, they need to provide an interface able to respond to local physiological and biological changes and to remodel the extracellular matrix (ECM) in order to integrate with the surrounding native tissue. Scientists in Singapore have developed a new nanoscale biocomposite that brings researchers one step closer to mimicking the architecture of the ECM.

Feb 1st, 2007

Hyperthermia therapy, a form of cancer treatment with elevated temperature in the range of 41-45C, has been recently paid considerable attention because it is expected to significantly reduce clinical side effects compared to chemotherapy and radiotherapy and can be effectively used for killing localized or deeply seated cancer tumors. Accordingly, various forms of hyperthermia have been intensively developed for the past few decades to provide cancer clinics with more effective and advanced cancer therapy techniques. However, in spite of the enormous efforts, all the hyperthermia techniques introduced so far were found to be not effective for completely treating cancer tumors. The low heating temperature owing to the heat loss through a relatively big space gap formed between targeted cells and hyperthermia agents caused by the hard to control agent transport, as well as killing healthy cells attributed to the difficulties of cell differentiations by hyperthermia agents, are considered as the main responsibilities for the undesirable achievements. In a possible breakthrough, researchers in Singapore now report the very promising and successful self-heating temperature rising characteristics of NiFe2O4 nanoparticles. Different from conventional magnetic hyperthermia, in-vivo magnetic nanoparticle hyperthermia is expected to be one of the best solutions for killing tumor cells which are deeply seated and localized inside the human body.

Hyperthermia therapy, a form of cancer treatment with elevated temperature in the range of 41-45C, has been recently paid considerable attention because it is expected to significantly reduce clinical side effects compared to chemotherapy and radiotherapy and can be effectively used for killing localized or deeply seated cancer tumors. Accordingly, various forms of hyperthermia have been intensively developed for the past few decades to provide cancer clinics with more effective and advanced cancer therapy techniques. However, in spite of the enormous efforts, all the hyperthermia techniques introduced so far were found to be not effective for completely treating cancer tumors. The low heating temperature owing to the heat loss through a relatively big space gap formed between targeted cells and hyperthermia agents caused by the hard to control agent transport, as well as killing healthy cells attributed to the difficulties of cell differentiations by hyperthermia agents, are considered as the main responsibilities for the undesirable achievements. In a possible breakthrough, researchers in Singapore now report the very promising and successful self-heating temperature rising characteristics of NiFe2O4 nanoparticles. Different from conventional magnetic hyperthermia, in-vivo magnetic nanoparticle hyperthermia is expected to be one of the best solutions for killing tumor cells which are deeply seated and localized inside the human body.

Jan 23rd, 2007

Silver has long been recognized for its infection-fighting properties and it has a long and intriguing history as an antibiotic in human health care. In ancient Greece and Rome, silver was used to fight infections and control spoilage. In the late 19th century, the botanist von Naegeli discovered that minute concentrations of silver contained microbiocidal properties. However, as the first antibiotics were discovered, this old household remedy was quickly forgotten. In an alarming trend, bacteria and other microorganisms that cause infections are becoming remarkably resilient and can develop ways to survive drugs meant to kill or weaken them. This antibiotic resistance is due largely to the increasing use of antibiotics. This led researchers to re-evaluate old antimicrobial substances such as silver. Silver nanoparticles have become the promising antimicrobial material in a variety of applications because they can damage bacterial cells by destroying the enzymes that transport cell nutrient and weakening the cell membrane or cell wall and cytoplasm. Unfortunately, in practical applications, the pure silver nanoparticles are unstable with respect to agglomeration. In most cases, this aggregation leads to the loss of the properties associated with the nanoscale of metallic particles. The stabilization of metallic colloids and thus the means to preserve their finely dispersed state is a crucial aspect to consider during their applications. Researchers in China have successfully demonstrated the use of a natural macroporous matrix for fabricating a stable, biocompatible nanocomposite with high silver content for antimicrobial purposes.

Silver has long been recognized for its infection-fighting properties and it has a long and intriguing history as an antibiotic in human health care. In ancient Greece and Rome, silver was used to fight infections and control spoilage. In the late 19th century, the botanist von Naegeli discovered that minute concentrations of silver contained microbiocidal properties. However, as the first antibiotics were discovered, this old household remedy was quickly forgotten. In an alarming trend, bacteria and other microorganisms that cause infections are becoming remarkably resilient and can develop ways to survive drugs meant to kill or weaken them. This antibiotic resistance is due largely to the increasing use of antibiotics. This led researchers to re-evaluate old antimicrobial substances such as silver. Silver nanoparticles have become the promising antimicrobial material in a variety of applications because they can damage bacterial cells by destroying the enzymes that transport cell nutrient and weakening the cell membrane or cell wall and cytoplasm. Unfortunately, in practical applications, the pure silver nanoparticles are unstable with respect to agglomeration. In most cases, this aggregation leads to the loss of the properties associated with the nanoscale of metallic particles. The stabilization of metallic colloids and thus the means to preserve their finely dispersed state is a crucial aspect to consider during their applications. Researchers in China have successfully demonstrated the use of a natural macroporous matrix for fabricating a stable, biocompatible nanocomposite with high silver content for antimicrobial purposes.

Jan 18th, 2007

Nanosurgery holds the promise of studying or manipulating and repairing individual cells without damaging the cell. For instance, nanosurgery could remove or replace certain sections of a damaged gene inside a chromosome; sever axons to study the growth of nerve cells; or destroying an individual cell without affecting the neighboring cells. While the cell nucleus has been transplanted between cells during cloning using micropipette technologies, these methods are too crude for other subcellular structures. First steps towards nanosurgery have been made using so-called 'optical tweezers', where the energy of laser light is used to trap and manipulate nanoscale objects, for instance the nucleus of a cell, without mechanical contact. Combined with a laser scalpel (use of lasers for cutting and ablating biological objects) optical tweezers have been used to study cell fusion, DNA-cutting, etc. Unfortunately, while optical tweezers offer exquisite sensitivity in their ability to position micro- and nanoparticles, they suffer from one important disadvantage: the trapped particle is localized at the laser focus where light intensity is the highest. As a result, the laser light used to trap a particle also has a propensity to photobleach and photodamage the particle, especially when the particle is fragile and small (e.g., a subcellular organelle that is fluorescently labeled). Minimizing this drawback, new research describes the use of polarization-shaped optical vortex traps for the manipulation of particles and subcellular structures.

Nanosurgery holds the promise of studying or manipulating and repairing individual cells without damaging the cell. For instance, nanosurgery could remove or replace certain sections of a damaged gene inside a chromosome; sever axons to study the growth of nerve cells; or destroying an individual cell without affecting the neighboring cells. While the cell nucleus has been transplanted between cells during cloning using micropipette technologies, these methods are too crude for other subcellular structures. First steps towards nanosurgery have been made using so-called 'optical tweezers', where the energy of laser light is used to trap and manipulate nanoscale objects, for instance the nucleus of a cell, without mechanical contact. Combined with a laser scalpel (use of lasers for cutting and ablating biological objects) optical tweezers have been used to study cell fusion, DNA-cutting, etc. Unfortunately, while optical tweezers offer exquisite sensitivity in their ability to position micro- and nanoparticles, they suffer from one important disadvantage: the trapped particle is localized at the laser focus where light intensity is the highest. As a result, the laser light used to trap a particle also has a propensity to photobleach and photodamage the particle, especially when the particle is fragile and small (e.g., a subcellular organelle that is fluorescently labeled). Minimizing this drawback, new research describes the use of polarization-shaped optical vortex traps for the manipulation of particles and subcellular structures.

Jan 16th, 2007

Gold nanoparticles have gained significant prominence in the design and development of nanoscale devices and nanosensors. The ubiquitous place of gold in nanoscience stems from its unique chemical property of serving in the unoxidized state at the nanoparticulate level. In sharp contrast, most of the surfaces of the less-noble metals are susceptible to oxidation to a depth of several nanometers or more, often obliterating the nanoscale properties. The high surface reactivity of gold nanoparticles, coupled with their biocompatible properties, has spawned major interest in the utility of gold nanoparticles for in vivo molecular imaging and therapeutic applications. The core of nanomedicine embodies high surface area and the size relationship of nanoparticles to cellular domains so that individual cells can be targeted for diagnostic imaging or therapy of cancer and other diseases. The development of biocompatible and non-toxic nanoparticles is of paramount importance for their utility in nanomedicine applications. Despite the huge potential for gold nanoparticle-based nanomedicinal products, nontoxic gold nanoparticle constructs and formulations that can be readily administered are still rare. Hypothesizing that the ability of plants to absorb and assimilate metals will provide opportunities to utilize plant extracts as nontoxic vehicles to stabilize and deliver nanoparticles for in vivo nanomedicinal applications, researchers now have used Gum Arabic as a plant-derived, nontoxic construct for stabilizing gold nanoparticles. The development of readily injectable, in vivo stable and non-toxic gold nanoparticulate vectors, especially built from currently accepted human food ingredients, would be pivotal in their many uses (e.g. in vivo sensors, photoactive agents for optical imaging, drug carriers, contrast enhancers in computer tomography, X-ray absorbers).

Gold nanoparticles have gained significant prominence in the design and development of nanoscale devices and nanosensors. The ubiquitous place of gold in nanoscience stems from its unique chemical property of serving in the unoxidized state at the nanoparticulate level. In sharp contrast, most of the surfaces of the less-noble metals are susceptible to oxidation to a depth of several nanometers or more, often obliterating the nanoscale properties. The high surface reactivity of gold nanoparticles, coupled with their biocompatible properties, has spawned major interest in the utility of gold nanoparticles for in vivo molecular imaging and therapeutic applications. The core of nanomedicine embodies high surface area and the size relationship of nanoparticles to cellular domains so that individual cells can be targeted for diagnostic imaging or therapy of cancer and other diseases. The development of biocompatible and non-toxic nanoparticles is of paramount importance for their utility in nanomedicine applications. Despite the huge potential for gold nanoparticle-based nanomedicinal products, nontoxic gold nanoparticle constructs and formulations that can be readily administered are still rare. Hypothesizing that the ability of plants to absorb and assimilate metals will provide opportunities to utilize plant extracts as nontoxic vehicles to stabilize and deliver nanoparticles for in vivo nanomedicinal applications, researchers now have used Gum Arabic as a plant-derived, nontoxic construct for stabilizing gold nanoparticles. The development of readily injectable, in vivo stable and non-toxic gold nanoparticulate vectors, especially built from currently accepted human food ingredients, would be pivotal in their many uses (e.g. in vivo sensors, photoactive agents for optical imaging, drug carriers, contrast enhancers in computer tomography, X-ray absorbers).

Subscribe to our Nanotechnology Spotlight feed

Subscribe to our Nanotechnology Spotlight feed