Showing Spotlights 25 - 32 of 43 in category All (newest first):

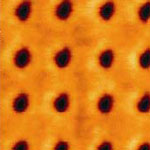

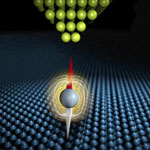

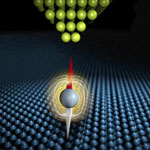

As technology keeps getting faster and smaller, the computer industry is working towards the end of the Moore's Law roadmap where technology will eventually be designed and created at the atomic level. Rather than working their way down incrementally, some researchers are taking a different approach by exploring what happens at the end of Moore's Law, specifically whether it is possible to do computing and other work at that scale. This means they are asking questions like, 'how many atoms are needed to store information', and 'are there schemes to do computation with magnetic atoms instead of transistors'? An IBM research team has now demonstrated, for the first time, the ability to measure how long an individual iron atom can hold magnetic information. They show how a scanning tunneling microscope can measure electron spin relaxation times of individual atoms adsorbed on a surface with nanosecond time resolution using an all-electronic pump-probe measurement scheme.

As technology keeps getting faster and smaller, the computer industry is working towards the end of the Moore's Law roadmap where technology will eventually be designed and created at the atomic level. Rather than working their way down incrementally, some researchers are taking a different approach by exploring what happens at the end of Moore's Law, specifically whether it is possible to do computing and other work at that scale. This means they are asking questions like, 'how many atoms are needed to store information', and 'are there schemes to do computation with magnetic atoms instead of transistors'? An IBM research team has now demonstrated, for the first time, the ability to measure how long an individual iron atom can hold magnetic information. They show how a scanning tunneling microscope can measure electron spin relaxation times of individual atoms adsorbed on a surface with nanosecond time resolution using an all-electronic pump-probe measurement scheme.

Sep 28th, 2010

After achieving the 45-nm process, today's semiconductor industry is nearing the 20-nm process and looking for techniques that would enable sub-22-nm-half-pitch line patterns. Following the continuous increase in exposure tool numerical aperture, researchers are pursuing reductions in exposure wavelengths. This effort had them look at extreme ultraviolet (EUV: 13.4 nm in wavelength) as an exposure light source. Unlike the numerical aperture engineering, change of a light source to EUV demands development of its related components, such as photoresist and optics. Until a reliable solution for EUV lithography is developed, EUV interference lithography (EUVIL) would not solely advance the lithographic technology but would also help to optimize photoresist materials for EUV.

After achieving the 45-nm process, today's semiconductor industry is nearing the 20-nm process and looking for techniques that would enable sub-22-nm-half-pitch line patterns. Following the continuous increase in exposure tool numerical aperture, researchers are pursuing reductions in exposure wavelengths. This effort had them look at extreme ultraviolet (EUV: 13.4 nm in wavelength) as an exposure light source. Unlike the numerical aperture engineering, change of a light source to EUV demands development of its related components, such as photoresist and optics. Until a reliable solution for EUV lithography is developed, EUV interference lithography (EUVIL) would not solely advance the lithographic technology but would also help to optimize photoresist materials for EUV.

Jul 8th, 2010

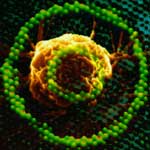

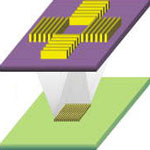

Even though traditional, digital computers have consistently increased in speed and complexity, they are limited by their reliance on sequential processing of instructions; i.e. no matter haw fast they are, they still process only one bit at a time. By contrast, individual neurons in our brain are very slow: they fire at only about 1000 times per second; however, since they are operating in a massively parallel way, with millions of neurons working collectively, they are able to complete certain tasks more efficiently than even the fastest super-computer. Another important distinction of our brain is that, during computing, information processing circuits evolve continuously to solve complex problems. An international research team from Japan and Michigan Technological University has now created a similar process of circuit evolution in an organic molecular layer, which also solves complex problems. This brain-like 'evolutionary' circuit has been realized for the first time in the world.

Even though traditional, digital computers have consistently increased in speed and complexity, they are limited by their reliance on sequential processing of instructions; i.e. no matter haw fast they are, they still process only one bit at a time. By contrast, individual neurons in our brain are very slow: they fire at only about 1000 times per second; however, since they are operating in a massively parallel way, with millions of neurons working collectively, they are able to complete certain tasks more efficiently than even the fastest super-computer. Another important distinction of our brain is that, during computing, information processing circuits evolve continuously to solve complex problems. An international research team from Japan and Michigan Technological University has now created a similar process of circuit evolution in an organic molecular layer, which also solves complex problems. This brain-like 'evolutionary' circuit has been realized for the first time in the world.

Apr 26th, 2010

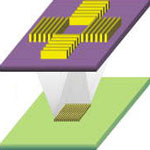

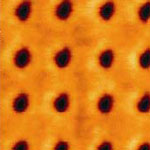

In developing next generation data storage devices, researchers are employing a variety of nanotechnology fabrication and patterning techniques such as electron-beam lithography, photolithography, microcontact printing, nanoimprinting and scanning probe microscope-based lithography. A decade ago, IBM for instance introduced the Millipede Project, a thermomechanical AFM-based nanopatterning technique that was aimed at data storage systems. While this system required an AFM tip heated to 350 degrees centigrade, researchers in Korea have now demonstrated that the writing, reading, and erasure of nanoscopic indentations on a polymeric film can be achieved by using an AFM tip at room temperature - no heating required.

In developing next generation data storage devices, researchers are employing a variety of nanotechnology fabrication and patterning techniques such as electron-beam lithography, photolithography, microcontact printing, nanoimprinting and scanning probe microscope-based lithography. A decade ago, IBM for instance introduced the Millipede Project, a thermomechanical AFM-based nanopatterning technique that was aimed at data storage systems. While this system required an AFM tip heated to 350 degrees centigrade, researchers in Korea have now demonstrated that the writing, reading, and erasure of nanoscopic indentations on a polymeric film can be achieved by using an AFM tip at room temperature - no heating required.

Sep 18th, 2009

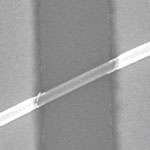

Experiments with graphene have revealed some fascinating phenomena that excite researchers who are working towards molecular electronics. It was found that graphene remains capable of conducting electricity even at the limit of nominally zero carrier concentration because the electrons don't seem to slow down or localize. This means that graphene never stops conducting. Taking advantage of the conducting properties of graphene, researchers now have described how graphene memory could potentially be used as a new type of memory that could significantly exceed the performance of current state-of-the-art flash memory technology. Their results show the possibility to build next-generation memory devices with vast amounts of memory using nanocables with a silicon dioxide core and a shell of stacked sheets of graphene.

Experiments with graphene have revealed some fascinating phenomena that excite researchers who are working towards molecular electronics. It was found that graphene remains capable of conducting electricity even at the limit of nominally zero carrier concentration because the electrons don't seem to slow down or localize. This means that graphene never stops conducting. Taking advantage of the conducting properties of graphene, researchers now have described how graphene memory could potentially be used as a new type of memory that could significantly exceed the performance of current state-of-the-art flash memory technology. Their results show the possibility to build next-generation memory devices with vast amounts of memory using nanocables with a silicon dioxide core and a shell of stacked sheets of graphene.

Nov 25th, 2008

The method that has been traditionally used in binary information storage is by making a distinction between storage (designated as 1) and non-storage (designated as 0). In reality, each imprint (or non-imprint) can store either 1 or 0. Thus the sequence and the numbers of 1 and 0 define everything with respect to the amount of information that can be stored and retrieved at the hardware level, no matter how sophisticated the overlaying software routines are. Ever since computers were developed, information storage has adhered to the eight-bit system. No matter how sophisticated information storage technologies have become - exploiting magnetoresistance, developing optical storage media such as CDs, DVDs and blue-ray discs, or the development of holographic storage media - a bit is always represented by manipulating a single feature, i.e., a transition or non-transition. Now, in contrast, consider the following: There are four colors, each of which could at least represent two or more bits; whereas in conventional methods only a single bit is available. In terms of color, this is somewhat similar to a black and white system that can support at most two kinds of transitions - 0 to 1 and 1 to 0. On the other hand, in four-color coded systems there can be 16 such unique transitions.

The method that has been traditionally used in binary information storage is by making a distinction between storage (designated as 1) and non-storage (designated as 0). In reality, each imprint (or non-imprint) can store either 1 or 0. Thus the sequence and the numbers of 1 and 0 define everything with respect to the amount of information that can be stored and retrieved at the hardware level, no matter how sophisticated the overlaying software routines are. Ever since computers were developed, information storage has adhered to the eight-bit system. No matter how sophisticated information storage technologies have become - exploiting magnetoresistance, developing optical storage media such as CDs, DVDs and blue-ray discs, or the development of holographic storage media - a bit is always represented by manipulating a single feature, i.e., a transition or non-transition. Now, in contrast, consider the following: There are four colors, each of which could at least represent two or more bits; whereas in conventional methods only a single bit is available. In terms of color, this is somewhat similar to a black and white system that can support at most two kinds of transitions - 0 to 1 and 1 to 0. On the other hand, in four-color coded systems there can be 16 such unique transitions.

Oct 23rd, 2008

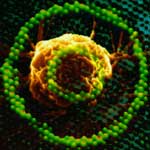

For nanoelectronics applications like single-electron devices to become practical, everyday items, they need to move from the highly individual and customized fabrication process typically found in laboratories to an automated, high-throughput and industrial-scale production environment. The reason this hasn't happened yet is that the various nanoscale pattern definition techniques used today - such as e-beam lithography, mechanically controllable break junctions, electromigration, electrodeposition, nanoscale oxidation, and scanning tunneling microscopy - generally are not suitable for large-scale parallel processing. The fabrication of single-electron devices requires nanoscale geometrical arrangement of device components, that is, source and drain electrodes and Coulomb islands. Developing methods to fabricate nanoscale devices in large numbers at a time has been one of the major efforts of the nanotechnology community. A new study now demonstrates that this can be done with complete parallel processing using CMOS-compatible processes and materials. Furthermore, these single-electron devices can operate at room temperature, an essential requirement for practical implementations.

For nanoelectronics applications like single-electron devices to become practical, everyday items, they need to move from the highly individual and customized fabrication process typically found in laboratories to an automated, high-throughput and industrial-scale production environment. The reason this hasn't happened yet is that the various nanoscale pattern definition techniques used today - such as e-beam lithography, mechanically controllable break junctions, electromigration, electrodeposition, nanoscale oxidation, and scanning tunneling microscopy - generally are not suitable for large-scale parallel processing. The fabrication of single-electron devices requires nanoscale geometrical arrangement of device components, that is, source and drain electrodes and Coulomb islands. Developing methods to fabricate nanoscale devices in large numbers at a time has been one of the major efforts of the nanotechnology community. A new study now demonstrates that this can be done with complete parallel processing using CMOS-compatible processes and materials. Furthermore, these single-electron devices can operate at room temperature, an essential requirement for practical implementations.

Sep 18th, 2008

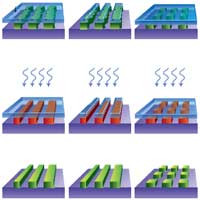

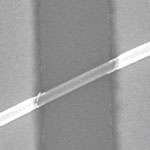

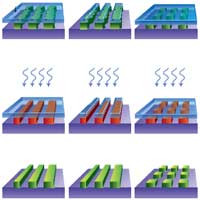

In the past, random defects caused by particle contamination were the dominant reason for yield loss in the semiconductor industry - defects occur in the patterning process (so-called process defects) when contaminants become lodged in or on the wafer surface. Trying to prevent such fabrication defects, chip manufacturers have spent much effort and money to improve the fabrication process, for instance by installing ultra-clean fabrication facilities. With the semiconductor industry's move to advanced nanometer nodes, and feature sizes approaches the limitation of the fabrication method used, particles are no longer the only problem for chip manufacturers. In a nanoscale feature-size fabrication environment, systematic variations, such as metal width and thickness variations or mask misalignment, are also major contributors to yield loss. Rather than perfecting a nanostructure by improving its original fabrication method, researchers at Princeton University have demonstrated a new method, known as self-perfection by liquefaction (SPEL), which removes nanostructure fabrication defects and improves nanostructures after fabrication.

In the past, random defects caused by particle contamination were the dominant reason for yield loss in the semiconductor industry - defects occur in the patterning process (so-called process defects) when contaminants become lodged in or on the wafer surface. Trying to prevent such fabrication defects, chip manufacturers have spent much effort and money to improve the fabrication process, for instance by installing ultra-clean fabrication facilities. With the semiconductor industry's move to advanced nanometer nodes, and feature sizes approaches the limitation of the fabrication method used, particles are no longer the only problem for chip manufacturers. In a nanoscale feature-size fabrication environment, systematic variations, such as metal width and thickness variations or mask misalignment, are also major contributors to yield loss. Rather than perfecting a nanostructure by improving its original fabrication method, researchers at Princeton University have demonstrated a new method, known as self-perfection by liquefaction (SPEL), which removes nanostructure fabrication defects and improves nanostructures after fabrication.

May 4th, 2008

As technology keeps getting faster and smaller, the computer industry is working towards the end of the Moore's Law roadmap where technology will eventually be designed and created at the atomic level. Rather than working their way down incrementally, some researchers are taking a different approach by exploring what happens at the end of Moore's Law, specifically whether it is possible to do computing and other work at that scale. This means they are asking questions like, 'how many atoms are needed to store information', and 'are there schemes to do computation with magnetic atoms instead of transistors'? An IBM research team has now demonstrated, for the first time, the ability to measure how long an individual iron atom can hold magnetic information. They show how a scanning tunneling microscope can measure electron spin relaxation times of individual atoms adsorbed on a surface with nanosecond time resolution using an all-electronic pump-probe measurement scheme.

As technology keeps getting faster and smaller, the computer industry is working towards the end of the Moore's Law roadmap where technology will eventually be designed and created at the atomic level. Rather than working their way down incrementally, some researchers are taking a different approach by exploring what happens at the end of Moore's Law, specifically whether it is possible to do computing and other work at that scale. This means they are asking questions like, 'how many atoms are needed to store information', and 'are there schemes to do computation with magnetic atoms instead of transistors'? An IBM research team has now demonstrated, for the first time, the ability to measure how long an individual iron atom can hold magnetic information. They show how a scanning tunneling microscope can measure electron spin relaxation times of individual atoms adsorbed on a surface with nanosecond time resolution using an all-electronic pump-probe measurement scheme.

Subscribe to our Nanotechnology Spotlight feed

Subscribe to our Nanotechnology Spotlight feed